Sharing is Caring: Abusing Shared Sections for Code Injection

In this article, we will explore how to abuse certain quirks of PE Sections to place arbitrary shellcode into the memory of a remote process without requiring direct process access.

Moving laterally across processes is a common technique seen in malware in order to spread across a system. In recent years, Microsoft has moved towards adding security telemetry to combat this threat through the "Microsoft-Windows-Threat-Intelligence" ETW provider.

This increased telemetry alongside existing methods such as ObRegisterCallbacks has made it difficult to move laterally without exposing malicious operations to kernel-visible telemetry. In this article, we will explore how to abuse certain quirks of PE Sections to place arbitrary shellcode into the memory of a remote process without requiring direct process access.

Background

Existing methods of moving laterally often involve dangerous API calls such as OpenProcess to gain a process handle accompanied by memory-related operations such as VirtualAlloc, VirtualProtect, or WriteProcessMemory. In recent years, the detection surface for these operations has increased.

For example, on older versions of Windows, one of the only cross-process API calls that kernel drivers had documented visibility into was the creation of process and thread handles via ObRegisterCallbacks.

The visibility introduced by Microsoft’s threat intelligence ETW provider has expanded to cover operations such as:

- Read/Write virtual memory calls (

EtwTiLogReadWriteVm). - Allocation of executable memory (

EtwTiLogAllocExecVm). - Changing the protection of memory to executable (

EtwTiLogProtectExecVm). - Mapping an executable section (

EtwTiLogMapExecView).

Other methods of entering the context of another process typically come with other detection vectors. For example, another method of moving laterally may involve disk-based attacks such as Proxy Dll Injection. The problem with these sort-of attacks is that they often require writing malicious code to disk which is visible to kernel-based defensive solutions.

Since these visible operations are required by known methods of cross-process movement, one must start looking beyond existing methods for staying ahead of telemetry available to defenders.

Discovery

Recently I was investigating the extents you could corrupt a Portable Executable (PE) binary without impacting its usability. For example, could you corrupt a known malicious tool such as Mimikatz to an extent that wouldn't impact its operability but would break the image parsers built into anti-virus software?

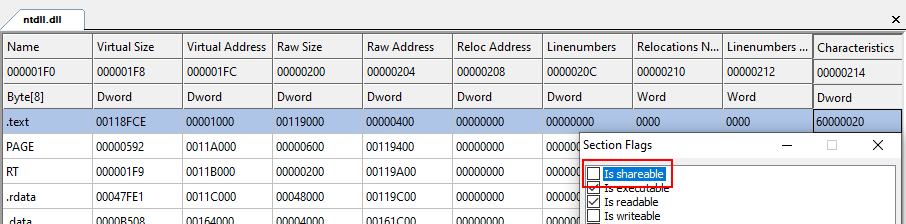

Similar to ELF executables in Linux, Windows PE images are made up of "sections". For example, code is typically stored in a section called .text, mutable data can be found in .data, and read-only data is generally in .rdata. How does the operating system know what sections contain code or should be writable? Each section has "characteristics" which defines how they are allocated.

There are over 35 documented characteristics for PE sections. The most common include IMAGE_SCN_MEM_EXECUTE, IMAGE_SCN_MEM_READ, and IMAGE_SCN_MEM_WRITE which define if a section should be executable, readable, and/or writeable. These only represent a small fraction of the possibilities for PE sections however.

When attempting to corrupt the PE section header, one specific flag caught my eye:

According to Microsoft's documentation, the IMAGE_SCN_MEM_SHARED flag means that "the section can be shared in memory". What does this exactly mean? There isn't much documentation on the use of this flag online, but it turned out that if this flag is enabled, that section's memory is shared across all processes that have the image loaded. For example, if process A and B load a PE image with a section that is "shared" (and writable), any changes in the memory of that section in process A will be reflected in process B.

Some research relevant to the theory we will discuss in this article is DLL shared sections: a ghost of the past by Gynvael Coldwind. In his paper, Coldwind explored the potential vulnerabilities posed by binaries with PE sections that had the IMAGE_SCN_MEM_SHARED characteristic.

Coldwind explained that the risk posed by these PE images "is an old and well-known security problem" with a reference to an article from Microsoft published in 2004 titled Why shared sections are a security hole. The paper only focused on the threat posed by "Read/write shared sections" and "Read/only shared sections" without addressing a third option, "Read/write/execute shared sections".

Exploiting Shared Sections

Although the general risk of shared sections has been known by researchers and Microsoft themselves for quite some time, there has not been significant investigation to the potential abuse of shared sections that are readable, writable, and executable (RWX-S).

There is great offensive potential for RWX-S binaries because if you can cause a remote process to load an RWX-S binary of your choice, you now have an executable memory page in the remote process that can be modified without being visible to kernel-based defensive solutions. To inject code, an attacker could load an RWX-S binary into their process, edit the section with whatever malicious code they want in memory, load the RWX-S binary into the remote process, and the changes in their own process would be reflected in the victim process as well.

The action of loading the RWX-S binary itself would still be visible to defensive solutions, but as we will discuss in a later section, there are plenty of options for legitimate RWX-S binaries that are used outside of a malicious context.

There are a few noteworthy comments about using this technique:

- An attacker must be able to load an RWX-S binary into the remote process. This binary does not need to contain any malicious code other than a PE section that is RWX-S.

- If the RWX-S binary is x86, LoadLibrary calls inside of an x64 process will fail. x86 binaries can still be manually mapped inside x64 processes by opening the file, creating a section with the attribute

SEC_IMAGE, and mapping a view of the section. - RWX-S binaries are not shared across sessions. RWX-S binaries are shared by unprivileged and privileged processes in the same session.

- Modifications to shared sections are not written to disk. For example, the buffer returned by both ReadFile and mapping the image with the attribute

SEC_COMMITdo not contain any modifications on the shared section. Only when the binary is mapped asSEC_IMAGEwill these changes be present. This also means that any modifications to the shared section will not break the authenticode signature on disk. - Unless the used RWX-S binary has its entrypoint inside of the shared executable section, an attacker must be able to cause execution at an arbitrary address in the remote process. This does not require direct process access. For example, SetWindowsHookEx could be used to execute an arbitrary pointer in a module without direct process access.

In the next sections, we will cover practical implementations for this theory and the prevalence of RWX-S host binaries in the wild.

Patching Entrypoint to Gain Execution

In certain cases, the requirement for an attacker to be able to execute an arbitrary pointer in the remote process can be bypassed.

If the RWX-S host binary has its entrypoint located inside of an RWX-S section, then an attacker does not need a special execution method.

Instead, before loading the RWX-S host binary into the remote process, an attacker can patch the memory located at the image's entrypoint to represent any arbitrary shellcode to be executed. When the victim process loads the RWX-S host binary and attempts to execute the entrypoint, the attacker's shellcode will be executed instead.

Finding RWX-S Binaries In-the-Wild

One of the questions that this research attempts to address is "How widespread is the RWX-S threat?". For determining the prevalence of the technique, I used VirusTotal's Retrohunt functionality which allows users to "scan all the files sent to VirusTotal in the past 12 months with ... YARA rules".

For detecting unsigned RWX-S binaries in-the-wild, a custom YARA rule was created that checks for an RWX-S section in the PE image:

import "pe"

rule RWX_S_Search

{

meta:

description = "Detects RWX-S binaries."

author = "Bill Demirkapi"

condition:

for any i in (0..pe.number_of_sections - 1): (

(pe.sections[i].characteristics & pe.SECTION_MEM_READ) and

(pe.sections[i].characteristics & pe.SECTION_MEM_EXECUTE) and

(pe.sections[i].characteristics & pe.SECTION_MEM_WRITE) and

(pe.sections[i].characteristics & pe.SECTION_MEM_SHARED) )

}All this rule does is enumerate a binaries' PE sections and checks if it is readable, writable, executable, and shared.

When this rule was searched via Retrohunt, over 10,000 unsigned binaries were found (Retrohunt stops searching beyond 10,000 results).

When this rule was searched again with a slight modification to check that the PE image is for the MACHINE_AMD64 machine type, there were only 99 x64 RWX-S binaries.

This suggests that RWX-S binaries for x64 machines have been relatively uncommon for the past 12 months and indicates that defensive solutions may be able to filter for RWX-S binaries without significant noise on protected machines.

In order to detect signed RWX-S binaries, the YARA rule above was slightly modified to contain a check for authenticode signatures.

import "pe"

rule RWX_S_Signed_Search

{

meta:

description = "Detects RWX-S signed binaries. This only verifies that the image contains a signature, not that it is valid."

author = "Bill Demirkapi"

condition:

for any i in (0..pe.number_of_sections - 1): (

(pe.sections[i].characteristics & pe.SECTION_MEM_READ) and

(pe.sections[i].characteristics & pe.SECTION_MEM_EXECUTE) and

(pe.sections[i].characteristics & pe.SECTION_MEM_WRITE) and

(pe.sections[i].characteristics & pe.SECTION_MEM_SHARED) )

and pe.number_of_signatures > 0

}Unfortunately with YARA rules, there is not an easy way to determine if a PE image contains an authenticode signature that has a valid certificate that has not expired or was signed with a valid timestamp during the certificate's life. This means that the YARA rule above will contain some false positives of binaries with invalid signatures. Since there were false positives, the rule above did not immediately provide a list of RWX-S binaries that have a valid authenticode signature. To extract signed binaries, a simple Python script was written that downloaded each sample below a detection threshold and verified the signature of each binary.

After this processing, approximately 15 unique binaries with valid authenticode signatures were found. As seen with unsigned binaries, signed RWX-S binaries are not significantly common in-the-wild for the past 12 months. Additionally, only 5 of the 15 unique signed binaries are for x64 machines. It is important to note that while this number may seem low, signed binaries are only a convenience and are certainly not required in most situations.

Abusing Unsigned RWX-S Binaries

Patching Unsigned Binaries

Given that mitigations such as User-Mode Code Integrity have not experienced widespread adoption, patching existing unsigned binaries still remains a viable method.

To abuse RWX-S sections with unsigned binaries, an attacker could:

- Find a legitimate host unsigned DLL to patch.

- Read the unsigned DLL into memory and patch a section's characteristics to be readable, writable, executable, and shared.

- Write this new patched RWX-S host binary somewhere on disk before using it.

Here are a few suggestions for maintaining operational security:

- It is recommended that an attacker does not patch an existing binary on disk. For example, if an attacker only modified the section characteristics of an existing binary and wrote this patch to the same path on disk, defensive solutions could detect that an RWX-S patch was applied to that existing file. Therefore, it is recommended that patched binaries be written to a different location on disk.

- It is recommended that an attacker add other patches besides just RWX-S. This can be modifying other meaningless properties around the section's characteristics or modifying random parts of the code (it is important that these changes do not appear malicious). This is to make it harder to differentiate when an attacker has specifically applied an RWX-S patch on a binary.

Using Existing Unsigned Binaries

Creating a custom patched binary is not required. For example, using the YARA rule in the previous section, an attacker could use any of the existing unsigned RWX-S binaries that may be used in legitimate applications.

Abusing Signed RWX-S Binaries in the Kernel

Although there were only 15 signed RWX-S binaries discovered in the past 12 months, the fact that they have a valid authenticode signature can be useful during exploitation of processes that may require signed modules.

One interesting signed RWX-S binary that the search revealed was a signed driver. When attempting to test if shared sections are replicated from user-mode to kernel-mode, it was revealed that the memory is not shared, even when the image is mapped and modified by a process in Session 0.

Conclusion

Although the rarity of shared sections presents a unique opportunity for defenders to obtain high-fidelity telemetry, RWX-S binaries still serve as a powerful method that break common assumptions regarding cross-process memory allocation and execution. The primary challenge for defenders around this technique is its prevalence in unsigned code. It may be relatively simple to detect RWX-S binaries, but how do you tell if it is used in a legitimate application?